India's Demographic Dividend

|

September, 2011

By Anumita Raj

|

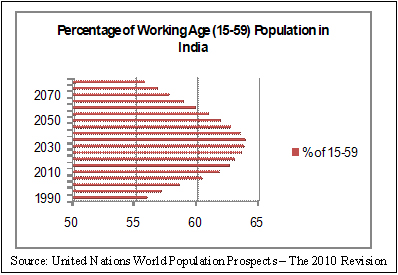

Like many developing countries at present, India will have a relatively large working-age population (aged between 15 and 59 years), as compared to its dependent population (aged 0-14 and 60+) over the next few decades. This "youth bulge" will reach its peak in the year 2035. Analysts consider this period of a "youth bulge"to be a boom, during which the abundance of human capital can be used to fuel the growth of the country.

Certain factors can impede the full exploitation of this demographic dividend. First, the level and quality of education will obviously have a significant impact on employability of Indians in the coming years. In the past few years, there has been an uptick in interest from both public and private enterprises to fill this gap. Approximately 12.4% of 240 million school-aged children in India were able to get through schooling to the college level in 2010, according to Kapil Sibal, the present Minister for Human Resources and Development. The Government of India aims to increase this number to 30% by 2020. However, the government will have to contend with high dropout rates (as high as 46% before middle school at the national level), as well as subpar education quality in many parts of the country. Moreover, even if the targeted numbers of students are able to get to the college level, there aren't adequate numbers of quality institutions in the country to cope up with the influx of students. Given the scale of the population confronting the government, quick action and results are unlikely.

Another challenge facing India will be preparing for the eventual aging of its population. Like many other developing countries with a large population (for example, Indonesia), most of India's working age population is employed in the informal sector; close to 300 million Indian workers at present belong to this sector. This means that most of this section of the population likely lives a hand-to-mouth existence, with few managing to save for future expenditures such as health crises or the higher education of their offspring. This coupled with a lack of access to banking and financial advice means that they mostly do not have adequate savings and investments to act as a safety net for when they are older, despite having worked for most of their life. This in turn will create an enormous burden on the government. This same phenomenon has already been noticed in countries like Indonesia. Government programs such as Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (health insurance) and Swavalamban (pension scheme) are recent steps in the direction of preventing such an occurrence. However, no scheme can cover the entire population at risk here.

There is a lot of scope to intervene at present to ensure that this demographic dividend is not wasted. Much of this burden will rest on the government, as well as on private enterprises, especially when it comes to generating employment opportunity. As the scope of the problem will be sizable, so too will have to be the scope of the intervention, which the government cannot manage on its own. This is an area where there is a lot of potential for public private partnerships between government agencies and institutions at all levels, including NGOs and foundations. Increasing access of people presently in the working age to vocational education and skills training facilities could prove to be an enormous benefit, as they will learn valuable and lucrative skills, while at the same time the government can manage to fill any skill or employment gaps that it has presently. Moreover, emerging industries (such as green technology) can use this as a recruitment tool for their industry. At the same time, it will be vital to provide financial and savings advice to working adults in order to encourage them to save and invest in their future.

India's youth bulge could just as easily turn into a youth bomb. If policies are implemented ineffectually, or are not enough to cater to a large enough section of the population, the result will be an over-abundance of young people who have not been educated adequately and are unemployed or under-employed. This in turn could build resentment as well as force this section of the population into illicit activities leading to a rise in crime and terrorism. Given that India's working age population will continue to be over 50% of the total population till the end of the 21st century, there is enough time to exploit it fully for the benefit of the country.

Related Publications

-

.jpg&maxw=50)

Big Questions of Our time: The World Speaks, 2016

Download:Big Questions of Our time: The World Speaks _Full Report

-

-

Second Freedom South Asian Challenge 2005-2025, 2005

read more

Download:Second Freedom South Asian Challenge 2005-2025 Full Report

Related latest News

Related Conferences Reports

-

Global Challenges Conference, October 2016

Download:Global Challenges Conference Report

-

Conference on Responsibility to the Future: Business, Peace and Sustainability, June, 2008

Download:Global Security and Economy: Emerging Issues